Mardi Gras Archive: Final update of this page completed in 2009 by David Simpson.

Mardi Gras in rural Southwestern Louisiana draws on traditions that are centuries old. Revelers go from house to house begging to obtain the ingredients for a communal meal. They wear costumes that conceal their identity and that also parody the roles of those in authority. They escape from ordinary life partly through the alcohol many consume in their festive quest, but even more through the roles they portray. As they act out their parts in a wild, gaudy pageant, they are escaping from routine existence, freed from the restraints that confine them every other day in the year.

| These traditions, folklorists say, go back at least as far as medieval times. The human impulse that underlies Mardi Gras has not diminished today, even if some of the traditions lapsed for decades and even if one factor in their revival by subsequent generations was a desire to enhance tourism. Anyone who has seen the procession of Mardi Gras riders brightly costumed in myriad colors advancing across the drab late-winter countryside is also likely to be swept up in the timeless moment: in rural Acadiana, Mardi Gras lives as much today as it did in centuries past. |  |

According to folklorist Barry Ancelet in his excellent monograph "Capitaine, voyage ton flag": The Traditional Cajun Country Mardi Gras, the Mardi Gras courir or run was found in most French sections of Louisiana in the nineteenth century. As they went from one household to the next, the riders engaged in a rowdy celebration that, with the civilizing influences of the twentieth century, some towns decided to suppress. In the early 1950s, as part of the effort by Paul Tate, Revon Reed, and others in Mamou to preserve Cajun culture, the Mardi Gras courir was revived. They also revived "La Chanson de Mardi Gras," a song echoing medieval melodies still remembered by a few old-timers: "Capitaine, Capitaine, voyage ton flag. / Allons se mettre dessus le chemin. / Capitaine, Capitaine, voyage ton flag. / Allons aller chez l'autre voisin." ("Captain, Captain, wave your flag. / Let's take to the road. / Captain, Captain, wave your flag. / Let's go to the other neighbors.")

The Tee-Mamou courir never lapsed, and the Eunice run was suspended only during World War II when many of the runners were in the service, but the revival of the runs in Mamou and Church Point seems to have been a key development in the growing popularity of the courir. In 1968, Elton Richard of Church Point and State Senator Paul Tate of Mamou flipped a coin which determined that the Church Point run would be on Sunday and the Mamou run on Mardi Gras Day. As these runs grew in size and the run in Eunice also grew, other communities have organized or revived runs.

|

In all of the Mardi Gras runs in rural Acadiana today, the capitaine maintains control over the Mardi Gras, as the riders are known. He issues instructions to the riders as they assemble early in the morning and then leads them on their run. When they arrive at a farm house, he obtains permission to enter private property, after which the riders may charge toward the house, where the Mardi Gras sing, dance, and beg until the owner offers them an ingredient for a gumbo. Often, the owner will throw a live chicken into the air that the Mardi Gras will chase, like football players trying to recover a fumble. Click here to download MP3 files of Mardi Gras songs recorded in Basile, Church Point, and the Mardi Gras chant in Soileau. |

In addition to the Mardi Gras on horseback, some ride on flatbed trailers pulled by trucks or tractors. In the Tee-Mamou courir that goes through countryside where the farm houses are widely separated, the Mardi Gras ride in a converted cattle trailer. The Basile run also uses trailers.

By mid to late afternoon, the courir returns to town and parades down the main street on the way to the location where the evening gumbo will be prepared.

|

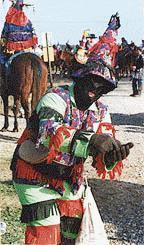

Mardi Gras wear all kinds of masks, including traditional masks that go back centuries: the high pointed conical hats or capuchons that parody the headress of noble ladies and that are also associated with dunces; masks with animal features, often with hair or fur; bishop's mitres parodying the clerical nobility; and mortarboards,as shown at left (worn by a Mamou Mardi Gras in 1998). |

This rider in the Mamou courir has a capuchon and an animal mask. |

Notice the hair flowing around a beak in this mask, also in Mamou. |

This mask, worn by a rider in the Eunice courir, parodies a bishop's mitre. |

| In earlier, more impoverished times, when the Mardi Gras re-enacted the medieval tradition of a procession of beggars, they might very well have needed help from farmers to get the ingredients for their gumbo. Today, the Mardi Gras still carry on the tradition of begging. |  This Mardi Gras in the Eunice courir

successfully begged for a quarter in exchange for posing for this picture. This Mardi Gras in the Eunice courir

successfully begged for a quarter in exchange for posing for this picture. |

|

Mardi Gras like to climb trees. Whether they are symbolically associating themselves with the tree of life, carrying out some ancient fertility ritual, or just playing around, it's part of the fun of a rural courir. |

LSUE's Mardi Gras pages do not claim to be comprehensive, not even for the parishes covered by the Central Acadiana Gateway. Other communities have organized runs in addition to the runs included here. Other towns have parades, Mardi Gras dances and balls, and additional activities. Elsewhere in South Louisiana, Mardi Gras in the City of Lafayette includes New Orleans-style parades.

|

The wild escape from the ordinary cares of life offered by Mardi Gras can only be understood in juxtaposition with Ash Wednesday and its reminder of earthly mortality. The LSUE Catholic Student Center is always overflowing with students on Ash Wednesday. The photograph at left is from 1997, when Father Ken Domingue imposed ashes and celebrated mass. Each year, Lent is observed by many Catholics in Acadiana with acts of penance or discipline in preparation for the celebration of Easter and its promise of spiritual immortality. |

A Note on Source Material. In addition to his monograph "Capitain, voyage ton flag" (1989), published by the University of Southwestern Louisiana's Center for Louisiana Studies, Dr. Barry Ancelet covers the same topics about Mardi Gras in Cajun Country (1991), coauthored by Jay Edwards and Glen Pitre and published by the University Press of Mississippi in its Folklife in the South Series. The same press has published Cajun Mardi Gras Masks (1997), focusing primarily on Tee-Mamou and Basile. The book, written by Carl Lindahl and Carolyn Ware, contains many vivid color photographs. Carolyn Ware went on to write Cajun Women and Mardi Gras: Reading the Rules Backward (University of Illinois Press, 2007), focusing on the Tee-Mamou and Basile women. A scholarly study that includes an extensive bibliography, the book should also be of interest to a general audience. Pat Mire's documentary film Dance for a Chicken: The Cajun Mardi Gras is an excellent account of Mardi Gras in a number of Acadiana communities. The Louisiana State Museum has a web page on Mardi Gras courirs. LSUE's Folklore Series from the 1990s also contains information on Mardi Gras traditions (including interviews on costumes and the Eunice courir in the third volume published in 1997).

Prepared by David Simpson.

Return to Central Acadiana Gateway

Updated April 2009.